Observers have posed the question of whether India will outstrip China in becoming the next global powerhouse, especially in light of India surpassing China in April to become the world’s most populous nation.

At first glance, factors like India’s higher birth rate and its ability to outpace China in terms of economic growth seem promising.

However, it is crucial to consider four inconvenient realities before drawing conclusions.

To begin with, analysts have previously misjudged India’s ascent. The 1990s saw optimism regarding India’s burgeoning youthful population driving economic liberalization.

As said firstly, analysts have been mistaken about India’s rise in the past.

In the 1990s, there was optimism about India’s growing youthful population driving economic liberalization and creating an “economic miracle.”

Similar sentiments emerged again in 2006, but the predictions made at that time did not materialize.

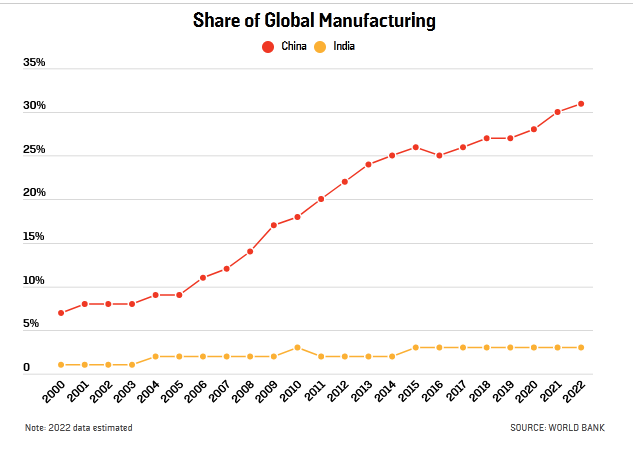

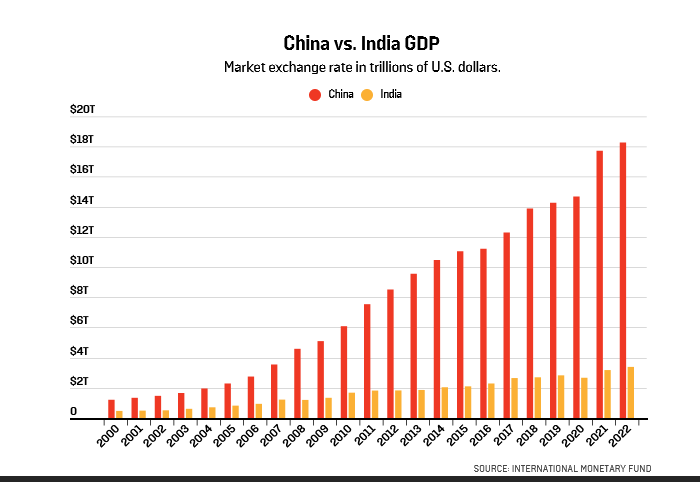

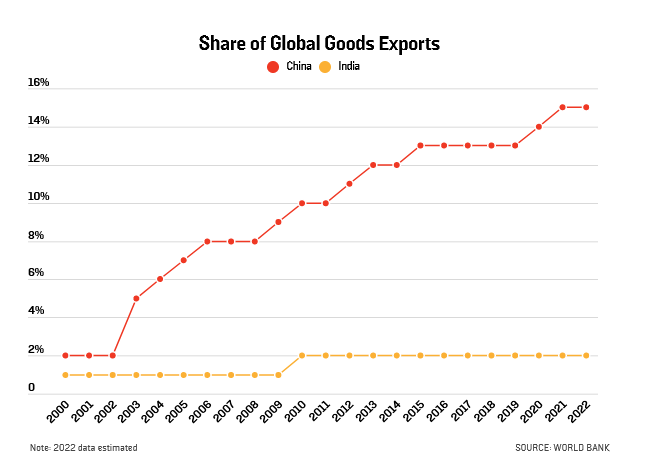

Secondly, despite India’s recent impressive growth and its inclusion among the world’s five largest economies, its economy remains significantly smaller than China’s. In the early 2000s, China’s manufacturing, exports, and GDP were already two to three times larger than India’s.

Currently, China’s economy is about five times larger, with a GDP of $17.7 trillion compared to India’s GDP of $3.2 trillion.

These two points highlight the importance of considering long-term trends and structural differences between the two countries.

While India’s growth has been notable, China’s economic advantage and its past achievements cannot be overlooked.

Similarly, in 2006, comparable sentiments were voiced, but the projected outcomes failed to materialize. Secondly, notwithstanding India’s recent remarkable growth and its inclusion among the world’s five largest economies, its economy still pales in comparison to China’s.

During the early 2000s, China’s manufacturing, exports, and GDP were already two to three times larger than India’s.

- Maintaining a professional tone, let’s carefully consider these factors before forming any hasty conclusions.

- Moreover, India’s advancement in the realm of science and technology, crucial for driving economic growth, has witnessed a significant setback.

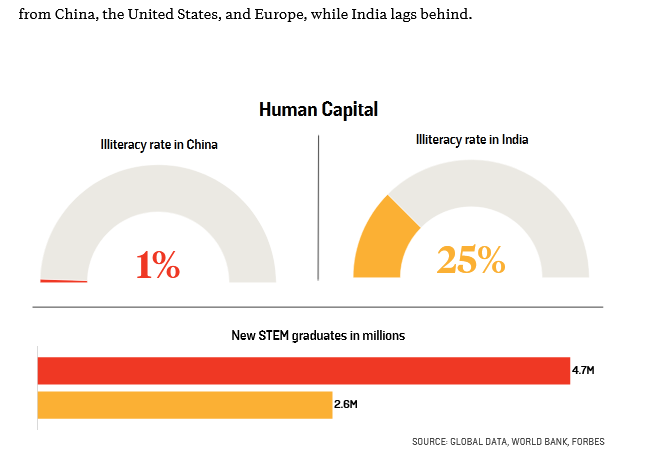

- A noteworthy discrepancy can be observed in the number of STEM graduates between China and India, with China outstripping India by nearly twice the count.

- Another significant disparity lies in research and development expenditure, as China allocates 2 percent of its GDP towards this domain, whereas India merely devotes 0.7 percent.

Additionally, when evaluating the global landscape, Chinese technological prowess is exemplified by the presence of four out of the top 20 tech companies in terms of revenue, while India fails to secure any spot within this esteemed group.

The influence extends to the field of telecommunications infrastructure, where China holds over half of the world’s 5G resources, while India’s contribution remains restricted to a mere 1 percent.

Furthermore, the global leadership demonstrated by Chinese-originated applications like TikTok starkly contrasts India’s limited success in creating a tech product capable of making a global impact.

It is worth noting that China stands as the sole global competitor to the United States in the area of artificial intelligence (AI) production.

China’s SenseTime AI model has demonstrated superior technical performance compared to OpenAI’s GPT, marking a significant achievement.

Conversely, India is currently absent from this competitive landscape. It is worth noting that China’s dominance in the field of artificial intelligence is further affirmed by its possession of 65 percent of the world’s AI patents, in stark contrast to India’s mere 3 percent stake.

Moreover, China has outpaced India in terms of private investments received by AI firms, with an impressive $95 billion recorded from 2013 to 2022, whereas India has procured only $7 billion.

Notably, prominent AI researchers predominantly hail from China, the United States, and Europe, further highlighting India’s comparatively lesser impact in this domain.

In evaluating a country’s strength, the quality of its workforce holds greater significance than its population size.

China stands out in this regard, as its workforce displays higher levels of productivity compared to India. The global community has rightfully hailed China’s remarkable achievement in reducing extreme poverty to a large extent.

In contrast, India still grapples with persistently high levels of poverty and malnutrition. In 1980, a staggering 90 percent of China’s one billion citizens lived below the World Bank’s abject poverty threshold.

Presently, the aforementioned figure is close to negligible. However, it is disconcerting that more than 10 percent of India’s colossal population of 1.4 billion still endure destitution below the World Bank’s defining threshold of extreme poverty, set at $2.15 per day.

Furthermore, recent data from the United Nations State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report reveals that from 2019 to 2021, approximately 16.3 percent of India’s populace suffered from undernourishment, while China’s corresponding figure was less than 2.5 percent.

Regrettably, India also grapples with alarmingly high rates of child malnutrition, which positions it unfavorably on the global scale.

Fortunately, the future does not always mirror the past. However, it is crucial to bear in mind the cautionary message conveyed by a Pentagon sign: Hope is not a viable strategy.

As the United States endeavors to support India under able Prime Minister Modi in accomplishing a more promising tomorrow, it is equally imperative for Washington to contemplate the assessment of Asia’s most insightful strategist.

The esteemed Lee Kuan Yew, the founding father and esteemed leader of Singapore, held Indians in high regard.

However, in a series of interviews published in 2014 prior to his demise, Lee provided an explanation that suggested he reluctantly came to the conclusion that this scenario was improbable.

Based on his analysis, Lee identified India’s entrenched caste system, which opposed the idea of meritocracy, its extensive bureaucracy, and the unwillingness of its elites to address the conflicting demands of its diverse ethnic and religious groups, as factors that would prevent India from surpassing its status as “the country of the future.”

Therefore, when questioned specifically if India could emulate China in the future, his response was firm: “India and China should not be mentioned in the same context.”

Since Lee provided this assessment, India has commenced a comprehensive infrastructure and development program under fresh leadership, illustrating its ability to accomplish substantial economic growth.

Although there is room for optimism that this occasion might diverge from the past, personally, I hold the belief that Lee would not place any wagers on it.

Ravi Singh – Chief Editor HNT